Caricature of Arthur Wing Pinero by Max Beerbohm, 1906

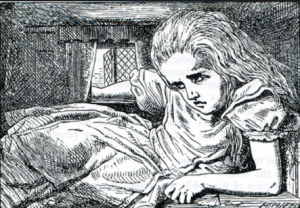

Max Beerbohm, an English parodist, often drew caricatures of late Victorian political, literary, and theatrical personalities. One of his subjects was Arthur Pinero, a contemporary English actor and director. I was drawn to this window image because of the physical impossibilities of the man’s frame. His elongated nose, enormous eyebrows, and tiny feet reminded me of Carroll’s manipulation of bodily size in Alice. From her serpentine neck to her giant growth, Alice takes on similarly nonsensical forms in Tenniel’s illustrations. Additionally, Tim Burton’s portrayal of the Mad Hatter also came to mind when considering the caricature. However, I think the primary effect between the art of Beerbohm and that of Tenniel and Burton differs. While Beerbohm’s caricature exaggerates Pinero’s actually large nose and eyebrows for comedic effect, Tenniel and Burton’s physical embellishments contribute to the otherworldly nature of Wonderland where anything is possible.

Manuscript of “Do not go gentle into that good night” by Dylan Thomas, ca. 1951

I was ecstatic when I first saw this image of Dylan Thomas’s manuscript because I really love the poem. But, after a moment, I reconsidered using the poem. After all, how could I connect a poem about resisting death to a little girl’s fantastical adventures in Wonderland?

After reading the poem a few times, I realized that the sadness it evokes reminds me of the sadness I felt when reading the final stanza of Carroll’s “Golden Afternoon” poem or the final page of Alice’s Adventures. Both deal with the loss and, in part, the death of childhood. At the end of Carroll’s first tale, Alice’s older sister reminisces on the wonder and magic of childhood imagination. Inducing potential despair, “she pictured to herself how this same little sister of hers would, in the after-time, be herself a grown woman” (AA 126). Of course, neither the sister nor the audience wants Alice to lose her wonderful imagination. Thus, just as Dylan addresses his dying father in his poem, the sister seems to be addressing Alice, silently wishing that Alice does not go into the “goodnight” of “dull reality,” but that she rage on with the “loving heart of her childhood” and continue “remembering her own child-life” (AA 126-27).